In my short series on the comprehensive reform of insolvency and restructuring law that came into force at the beginning of 2021 (see most recently here and here), I will in the following turn to early risk and crisis warning mechanisms. In the years since the financial crisis, this topic – at the interface with business resilience management (see most recently here) – has tended to lead a wallflower existence. Since the corona pandemic, however, all kinds of forecasts as the core of crisis and early risk detection are once again enjoying undivided attention, at least in the media.

Legal framework

It is true that the German “Corporate Stabilisation and Restructuring Act” (“Unternehmensstabilisierungs- und -restrukturierungsgesetz”, “StaRUG”) has now legally anchored an obligation to establish early crisis detection systems independently of the corporate form chosen. However, already the “KonTraG” of 1998 provided for the establishment of such systems for public limited companies in § 91 (2) AktG. According to the government’s plan at the time, this obligation was also supposed to have a “radiating effect” at least on larger limited liability companies. But it did not. As part of the implementation of the corresponding EU directive on the introduction of the “preventive restructuring framework” into German law (see most recently here), the obligation to set up risk/crisis early warning systems in companies was now introduced in § 1 StaRUG as of 1 January 2021. This obligation is supplemented and flanked by an explicit obligation to indicate the existence of reasons for insolvency pursuant to § 102 StaRUG for auditors, tax advisors, certified public accountants and lawyers in the context of the preparation of annual financial statements. In addition, the early risk detection system must (still) be explicitly audited in the context of the audit of the annual financial statements for public limited companies according to § 317 para. 4 HGB.

The aforementioned regulations, however, only presuppose the existence of early risk detection systems, but do not specify the concrete design. In this respect, the auditing standard of the auditors (IDW PS 340) corresponding to the regulation of § 91 AktG succinctly states:

“Effective risk identification, i.e. risk recognition and analysis, requires that both predefined risks and – as far as possible – anomalies or risks that do not correspond to a predefined appearance are recognised. This requires the creation and further development of an appropriate risk awareness among all employees, which is of particular importance in those areas which – depending on the individual company situation – are assessed as being particularly susceptible to risk.”

It is also true that § 101 StaRUG provides, in fulfilment of the requirements of Art. 3 (3) of the corresponding EU Directive (see here), that “information on the availability of the tools provided by public bodies for the early identification of crises shall be made available by the German Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection (BMJV) at its internet address www.bmjv.bund.de.” To date, however, nothing can be found on the BMJV website about such “instruments”. On the other hand, the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi) maintains two checklists that are supposed to help in setting up early crisis detection systems (the “Early Detection Staircase”, here (in German) and the “Checklist: Crash Test “Vulnerability Early Detection”, here (in German). These one-page documents may be useful as initial ideas, but they are not suitable for reasonably reliable early crisis and risk detection.

In other words, the entrepreneur is more or less left to his own devices when it comes to the concrete design of a crisis and risk early warning system for “his” company. The following is therefore intended to provide initial guidance on how to establish a company’s own risk and crisis early warning system.

Theoretical foundations of early crisis and risk detection

Despite the lack of corresponding public “instruments”, entrepreneurs interested in this topic have countless possibilities to inform themselves about the establishment of an effective system for early crisis and risk detection on German websites. But the number of specialist articles has also increased significantly since the introduction of the StaRUG (see only Sämisch, “Früherkennung – der Schlüssel zur effektiven Krisenbewältigung”, ZInsO 2021, 169, in German). The problem in this matter is more likely to be separating the wheat from the chaff.

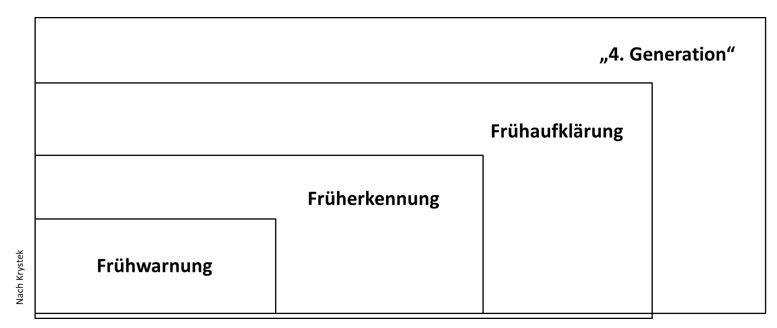

At this point, we will only briefly trace the “evolution” of (business) crisis and risk early warning systems, because this is a good way of indicating the potential development steps for entrepreneurs: risk and crisis early warning has developed from “early warning” to “early detection” to “(strategic) early detection” (for more details see Krystek/Moldenhauer, Handbuch “Krisen- und Restrukturierungsmanagement”, p. 97 ff.):

a) The “first generation” (“Frühwarnung“) of early risk and crisis detection, so-called “early warning systems”, were mostly based on simply structured quantitative key figure systems whose data came from the company’s internal accounting and balance sheet system. The serious weakness of this first generation is the exclusive reference to the past and the orientation towards “hard facts”.

b) The “second generation” (“Früherkennung“) of risk and crisis detection, the so-called “early detection”, is still a purely quantitative model, which, however, already took the weaknesses of the first generation into account insofar as it was based on leading (internal and external) indicators.

c) As the “third generation”, (“Frühaufklärung“) the “(strategic) early warning” became established. The dogmatic basis of this approach was laid by Ansoff in “Managing Strategic Surprise by Response to Weak Signals” in 1975 in the aftermath of the 1973 oil price shock. According to this approach, “weak signals” are poorly defined and fuzzily structured messages that indicate “strategic discontinuities” (trend changes/breaks) but, if relevant, become stronger over time.

d) After the initial distinction between so-called “strategic” and “operational” early warning, these two areas are now combined in the sense of a “fourth generation” (“4. Generation“) of early risk and crisis detection.

In the meantime, due to the constant ramification of the theoretical discussions, there is also a risk of “over-academisation” or further confusion due to the constant creation of new “buzzwords” by the multitudes of consultants. For this reason, here are some practical tips for developing a company’s own culture of early crisis and risk detection.

Early crisis and risk detection in business practice

As is so often the case, early crisis and risk detection in one’s own company is best not started with checklists (like those of the BMWi), but with the “mindset”. Even though in times of corona, climate change and supply chain problems the sense of a crisis and risk early warning system probably does not need to be explained to most entrepreneurs, it can often be observed that after the initial euphoria, everyday routine returns and entrepreneurial foresight is limited to a few thin formulations within the framework of the continuation forecast of the annual financial statement.

Therefore, as always, the orientation of the entrepreneurial “mindset” towards early crisis and risk detection is decisive for the successful establishment of the corresponding systems. And in case of doubt, this does not start with the installation of a company-internal “round table” or similar formal structures, but on the one hand with the analysis of the data already available in the company and regularly updated on the basis of the “generations” of crisis and early risk detection systems outlined above. Normally, the data for the establishment of a “first generation” should already be available in the company’s controlling; if necessary, they must still be regrouped as so-called “key performance indicators” (KPI).

On the other hand, people in the company should be identified who obviously (out of intrinsic motivation) deal with forecasting topics – e.g. the person who can refer to the current headlines from the various online media at any time. This is because these people, even without a special assignment, are more likely to deal with emerging “weak signals”, which are indispensable in the context of an evolving crisis and risk early warning system.

Finally, it is essential to understand crisis and risk early warning as a permanent process, as a cycle, and not as a one-off action. The bon-mot attributed to Mark Twain, “Forecasts are difficult, especially when they concern the future”, points to what we are all experiencing in the current pandemic: The (sometimes crashing) failure of forecasts to match the reality of life. Forecasting is a difficult business, but neither the “best” nor the “most accurate” or “most correct” forecast matters – for an entrepreneur the motto should rather be to be “better than the competitor”: “A company that is right three times out of five on its judgement calls, is going to have an ever-increasing edge on a competitor.” (Tetlock / Gardner, Superforecasting, p. 2; see also Schoemaker/Tetlock, “Superforecasting: How to Upgrade Your Company’s Judgement”, Harvard Business Review, May 2016, available here). And accordingly, the failure of one forecast should be the starting point and sufficient teaching material for the next.

Gesetz zur Fortentwicklung des Sanierungs- und Insolvenzrechts (Sanierungs- und Insolvenzrechtsfortentwicklungsgesetz – SanInsFoG) vom 22. Dezember 2020 (BGBl 2020, part I, p. 3256) (in German)

RegE eines Gesetzes zur Fortentwicklung des Sanierungs- und Insolvenzrechts (with extensive reasoning on the bill) (in German)

The above post is also in part a summary of Beissenhirtz, „Der Blick hinter die Glaskugel – Gedanken zur Risiko- und Krisenfrüherkennung in mittelständischen Unternehmen“, ZInsO 2020, 1673 (here) (in German)